It is doubtful if the Italian film-maker Frederico Fellini knew of the work of the Scottish luminary Patrick Geddes – biologist, ecologist, sociologist, educationalist and planner.

Fellini’s films have a strong sense of place, and of the relationship between people and place, which was an important theme for Geddes. I want to explore one of Fellini’s early films, Il Bidone, focusing on that relationship.

The black and white film, released in 1955, is about a con-man, Augusto, played by American actor Broderick Crawford. It features three successful swindles, interspersed with a scenes in which Augusto goes to a party, hangs out in a small town, and meets up with his daughter. For a fuller summary of the plot https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Il_bidone .

The film covers contrasting locations, but in each case the place expresses visually the spiritual and mental state of the characters. The objective landscape shapes and reflects the subjective world of people, their actions and their dreams, which is a theme Geddes developed.

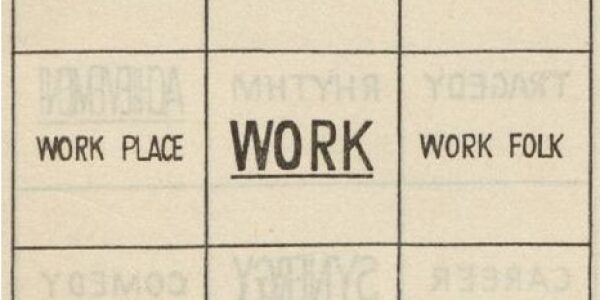

Early in the film, Augusto and his two less experienced assistants drive to a farmhouse, which stands alone in a rather bleak scrubby landscape. Disguised as a senior member of the Roman Catholic church, he gets two elderly sisters to hand over their life savings in the belief that this will allow them to keep a box of buried ‘treasure’ unearthed on their land by his accomplices. The faces of these poor simpletons reflect their poverty and the bare land from which they derive their existence. Similarly, their unquestioning gullibility in the face of the authority imbued by the garb of a priest is also a reflection of their vulnerable isolation from information and support. Place, work and folk are thus connected.

The second scam is undertaken in a totally different physical environment. Now in smart suits Augusto and his accomplices drive up a narrow lane in an area of informal housing squeezed under the arches of a viaduct. It is the polar opposite of an isolated farmhouse. This place teems with people who live in small, overcrowded houses. Their visitors claim to finally be housing officials, there to allocate houses in a new development, collecting deposits from those desperate to realise their dream of having somewhere decent to live. Traditional notions of community are evident – everyone knows everyone else, warts and all. However, with the prospect of a house dangled before them, people jostle each other to be first in line to get their name down, and hand over the little money they can lay their hands upon. Living on the breadline gives no room for consideration to others, but also breeds the ignorance that Augusto successfully exploits.

The city centre is also a crowded place, where chance interactions occur and business contacts are made. It is there, with a razzmatazz sound track, that Augusto meets a much more successful criminal friend who is driving a flashy car and who invites him to a party. The faces of the people at the party, unpinched by poverty, make a stark contrast with those in the farm or the shanties. The same is true for the nightclub that Augusto frequents, and where women work as dancers and prostitutes. Later in the film, in a bar, Augusto overhears a phone conversation, which leads him to contacts to set up the next con’ job. In another chance meeting on a city street, Augusto is recognised by his daughter, Patrizia, who he has not seen for months. The city is thus the place of social and economic contacts, where deals, commercial and criminal, are struck. It is the place of entertainment, learning (Patrizia is at college and needs money), and conspicuous consumption. At night it is the place where dreams can be pursued – the nightclub for Augusto, while one of his accomplices aspires to be a painter and takes one of his works to the party, while the third member of the gang dreams of being a successful singer. Augusto himself also imagines that he can be a bigger, better criminal than the amateurs he is working with, a sense emphasised in scenes in a small town at night. However, with daylight comes always reality, a world of facts and actions.

Finally, after reprising the clerical / treasure scam at another isolated farmhouse, Augusto seeks to conceal the money from his co-conmen and the Mr. Big to whom they are in tow. They turn on him and he is left paralysed and isolated in a desolate, stony valley which manifests his anguish.

There are other strong themes in the film, not least one about gender relations. While anti-clerical,it is also inspired by religion, with its themes of suffering, faith, family and redemption, exemplified by the closing scene and Augusto’s plaintive words, “Wait. I’m coming. I’m going with you”. However, if you view the film and listen to the musical soundtrack from a Geddesian angle, you see a depiction of Place-Work-Folk on screen.

![]()