The film The Square is about more than the excesses of contemporary art. It explores the conditions on which people are able to live in cities.

In his film The Square, director Ruben Östlund dissects the contemporary urban condition. Certainly squares are geometrical shapes, and the geometrical motif is one of several images and sounds that carefully knit this film together. Although the title refers to an art installation, and there are plenty of jokes about the pretentiousness of the art scene (“Mirrors and Piles of Gravel”), we should also recall the significance of public squares in the history of cities.

Throughout history, squares have been the very essence of the urban fabric, function and spectacle. They are the heart of cities from very different cultures – Ancient China, the Greeks’ agora, traditional Arab cities, or Western Europe. Like whole cities, cities’ squares are places where business is done, crowds are free to gather, people meet for all sorts of purposes, and information is exchanged. These squares are not part of the natural world, rather urban squares are artifices, built by people, knowingly and often with conceit, celebrations both of equity but also of power, whether that power is expressed in edges formed by the facades of baroque palaces or by the arena they provide for parades of military might.

As Murat Z. Memluk observed “Urban squares are open public spaces which reflect the cities’ identity and the communities’ cultural background. They are where people of the community gather and ‘urban life’ takes place since the ancient times. As the fundamental component of the city structure, urban squares contribute to the image and prestige of the city.” Connected in this way, The Square can be viewed as a metaphore for how we manage to live in big cities. Like the Covid 19 pandemic, it also shows us how fragile urban life is today.

Urban social contracts

The film’s pre-credit sequence begins with the muffled noise of a crowd. Östlund’s film is about the social contracts that make it possible for people to live harmoniously amongst thousands of strangers. The paradoxes are captured in a brilliant early sequence. Individuals pour out of a downtown metro station in Stockholm: absorbed in their mobile phones, and all heading in one direction, a sea of contemporary, affluent, urban Scandinavian humanity. They ignore the “chugger” who is asking “Do you want to save a human life?” In the distance at first, there is a cry for help, which gets more frantic and nearer, though few in the crowd pay attention until a man facing the other way appears and persuades the central character, Christian, curator of the art museum, to help him rescue a young woman. She flees towards them followed by an aggressive man. The situation is quickly defused, though Christian soon realises that he has been robbed.

So how deeply do you care about the cries for help that, as the film shows through sound and images, are ever present in today’s cities? Who do you trust and what kind of structures and assumptions have created comfort zones and threatening spaces? Christian traces his phone to a block of flats in a part of town very different from his own world. The depiction of his visit to this underworld (he drives through a long tunnel to get there) has all the edgy menace classically associated with Alfred Hitchcock films. In contrast to his anxiety and distrust, late in the film there is an exuberant display of team acrobatics by a troupe of young girls, another crowd, but one in which everyone has to work together and display absolute trust in each other.

To be in the square, whether in the city or in the art installation called “The Square”, we have to embrace equal rights and obligations for all. Yet that sense of solidarity is being eroded in today’s cities. The film points to some of the forces fraying the bonds that made cities what they are. Some of these are individual choices – the ubiquitous tones of a mobile phone, the car as a haven and means of escape, casual sex. Yet, as Christian is always ready to reassure himself, there are also societal forces beyond the individual, the widening inequalities and growing poverty and the digitalisation of life. There are so many cries for help, it is not always clear where they are coming from, let alone how to evaluate them

Beggars, now a common sight on big city streets, are often used as transition shots linking scenes in the film. The press wants a controversy, a statement about human kindness turns no pages. A lot of public money has to be spent to prevent massively rich people buying the best artworks, to make them accessible to all (though the audience for the preview suggests a narrow, affluent and white demographic). Art becomes marketing in making a You Tube video go viral by showing a young, homeless, blonde Swedish girl being blown up inside The Square – the horrible deaths of young girls in Syria or Yemen are now as familiar and unmoving as the chugger’s invitation to save a human life. The success of the video prompts a call from Pauline from You Tube’s marketing who has not seen the video but wonders if the museum wants to allow adverts with it, so as to “share partner revenue”. As Christian observes, there is just not the trust in other adults that there was in the days when a child could roam freely in the centre of a big city.

In the city you become part of the herd, sheltered by your anonymity, and by knowing little of the lives of others. You are absolved from morality – all you need to do is see which way the herd is going and follow it, or risk being the patsy. You feel a kind of guilt, but what can you do about it? These are the Janus faces of the sanctuary and freedom that are part of that same urban social contract.

The risk of chaos

Yet, the urban system is fragile. If people break the rules, written and unwritten, it will unravel. In the film a boy, wrongly and inadvertently accused of the robbery by Christian, bursts through the curator’s protective social barriers, and threatens to create “chaos” if he is denied “justice”. He can evoke that chaos simply by shouting in a convenience store or on the stairs up to Christian’s expensive-looking flat.

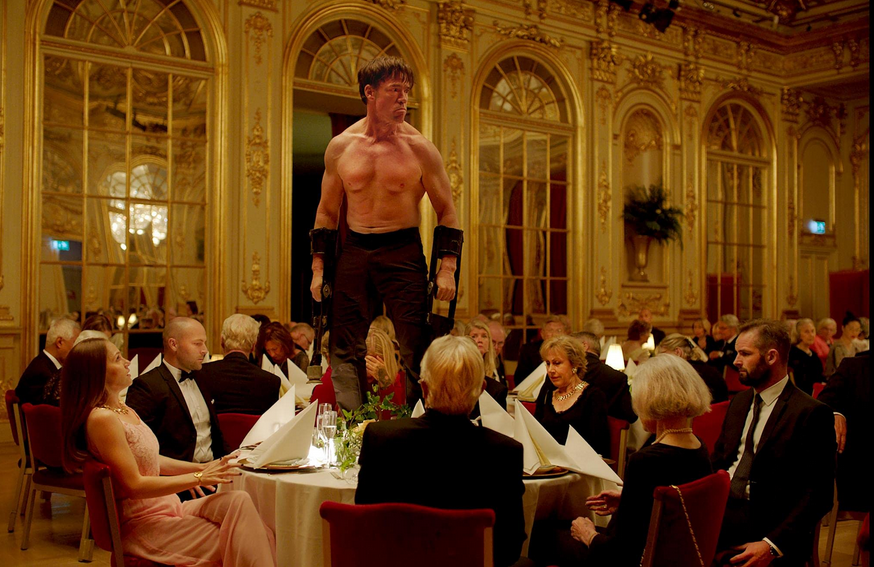

There are two other visually powerful exposures of the fragility of this comfortable world of Europe’s metropolitan arts world. In a central sequence, performance artist Oleg terrifies diners at a banquet by the ferocity of his animal battle for dominance. Like the boy, he overrides the rules. Oleg is the other, the outsider invited in to amuse and provoke; he is tolerated, naturally, until he goes too far, at which point the herd takes its revenge. The second, more enigmatic scene depicts Christian (seen from above, and so diminished) scrambling atop a pile of plastic bags, a mound of garbage, ripping bags open in a desperate search. The imagery evokes the kind of mounds of solid waste that can be part of the street scene in informal settlements and slums in poor countries. It hits at an apocalyptic collapse.

Relational aesthetics

As Christian explains art exists in relation to its audience, and how they react to what is exhibited. This is true of film as much as the installation art which The Square depicts. Different people from different backgrounds will respond to this, and other films, differently from me. As Östlund has said, his films are about thefear of losing face, and they puncture the vanities of successful middle-aged men.My background as a planner / urbanist shapes the way I have experienced his film, and others reviewed on this website. I am grateful to the over-60s, Zoom-based film group which formed after the coronavirus emergency closed Edinburgh Filmhouse. The group has given me the discipline of thinking and writing about some of the films we have viewed and discussed.

Other film reviews on this site:

Mr.Tree – A tale from the new China

Prefab’ Story – High Rise, Mud and Shoddy Housing

A Tale of Two Cities: Fellini’s Roma and Davies’ Liverpool

Community and Film – Akenfield and Byker

Force Majeure (by the same director as The Square)

![]()