Like many planners I am a fan of the movies, and especially fascinated by films where place is central to the narrative. Over the weekend I was lucky enough to see not one, but two films about cities. They have a lot of similarities but also many differences. They areFellini’s Roma and Terence Davies’ reflections on Liverpool, Of Time and the City. What do they tell us about today’s urban situation?

Of Time and The City

Of Time and the City is described as “a love song and a eulogy to Liverpool.” Davies was born in the city in 1945, and his 1988 film Distant Voices, Still Lives recreated the city and time in which he grew up. Made in 1988, Of Time and The City is less of a drama, more a visual, musical and poetic insight to place, class and time. It uses archive film overlaid with a personal narrative.

It is Liverpool as seen through the lives of its working class citizens. Mucky-faced kids play on the streets, and boats of all shapes and sizes jostle on waterfront while The Spinners sing Ewan Macall’s evocative Dirty Old Town (which is cut short before the lines that promise clearance and rebuilding). A day out means a deckchair crammed next to others on the beach at New Brighton, a sardine-packed “ferry across the Mersey” away. Bonfires crackle on 5 November as young and old “keep the home fires burning”.

Solidarity and class are embedded in the black and white fabric of the cobbled steets, the terraced houses and the shared work of mothers and of their men. Raw indignation bristles at the “Betty Windsor Show”, the technicoloured “vivat regina’s” of the Coronation. Wrapped around all of this is a Catholicism that dogmatically demands and diminishes, and cannot embrace Davies’ sexulaity.

The wreckers ball arrives, homes crash, bricks and slates tumble, and still in black and white, the municipal tower blocks stand proud, to the soundtrack of Peggy Lee singing The Folks Who Live on the Hill. As the narrator observes it was less than the paradise that had been expected. The rotting sense of powerlessness is echoed in the abandoned Albert Dock.

So as Davies ages the city changes in ways that become beyond comprehension, is taken away from him. The faces age with him, the boys and girls playing street games dance in The Cavern and become hobbling pensioners, while new generations follow, but with no more signs of hope.

Roma

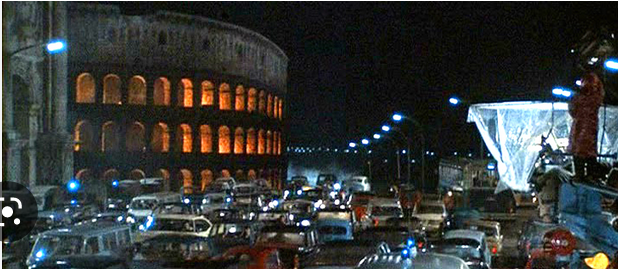

Fellini’s Roma was released in 1972, and begins when its director was a boy in Rimini in the late 1920s, so there are chronological overlaps but not symmetry between it and Davies’ Liverpool. Where Davies is pained with self-guilt and distances himself from the emergent Merseybeat pop culture, Fellini, the rumbustious extrovert ploughs through the 1970s modernisation of Rome, ogling hippies and ending with a dazzling cityscape of bikers and monuments.

Catholicism, so painful and repressive in black and white, appears here in bizarrely rich colours. There is a hilarious sequence where red frocked clergy are treated to a catwalk show of outrageous clerical outfits, lame, flashing neon lights and roller skates. And, this being Fellini, you are never far from a fat prostitute to ease the tensions of day to day living, whether during the rise of Mussolini or in the rain along the side of a 1970s autostrada.

An early sequence takes you into 1970s Rome along the highway. It reminded me of many a ride in today’s rapidly urbanising countries: chaotic traffic, ranging from huge lorries to handcarts, Mercedes and old bangers; random animals (some now carcasses, some weaving through the traffic); ineffectual traffic police half-heartedly doing an impossible job; and all leading remorselessly to a huge traffic jam, which in Roma is throttling the Coliseum.

Modernity is a subway system, but deep below ground the engineers and the film crew drill through to layers and layers of archaeology. The city is built on its past.

As in Liverpool, the city changes in ways that the old find difficult to comprehend or to accept. People are no longer as friendly as they were; cardinals don’t call around as often as they used to; and the sexual mores and drugs of the (1970s) young people are an affront to decency.

Global and Local

In their contrasting ways both films are intensely personal stories about cities as places whose blemishes are cherished. Both weave together place and time showing continuity and change, in people and place. At a time when planners talk frequently but loosely and superficially about “place-making”, both offer rich seams to be mined if we are to get a better understanding of the multiple dimensions of place.

The connection to the past can be read through the built environment in both Liverpool and Rome. It is there in their iconic buildings and public spaces, some classical, some neo-classical; through streetscapes of poverty and privilege; and in the arenas of the populous, whether a raucous Fellini music hall or the venue of the professional wrestling matches that so excited the teenage Davies’ sexuality.

Yet the global is also part of the place. Where did the wealth come from to construct the splendid columns and porticos that adorn the screen in the early part of Davies’ film? His elder brother’s service in the Korean War is seminal experience for Davies. And, of course, you can no longer make a living by unloading bananas down at the docks.

Meanwhile, Gore Vidal explains to Fellini that the “eternal city” is the best place to sit and wait for the end of the world that is being brought on by overpopulation and pollution. Earlier in the film, seemingly carefree Romans had entertained themselves by barracking music hall performers while news came through of Allied forces advancing in war-time Sicily.

For all their engagement with place, planners and urban designers rarely seem to consider what they can learn from artistic explorations of cities (or landscapes). These two films, in their contrasting ways, give us some insights.

![]()